catalogue text: Marta Jecu

EVERY PHOTOGRAPHIC ACT registers a centre: the self of the photographing body (the camera/ the photographer himself) places itself in a middle, from which it captures the black hole of the infinite 'here and now'. The absolute singularity of the machine's position in relation to reality is nevertheless not static: it is rapid, in movement, capturing at once a mechanical and psychic dynamics. When asked what does he feel when taking a photo, French photographer Denis Roche answered: 'Violence' (Roche 77).

'What we photograph is precisely the instant in which we take the photo. It is obvious that this is what we photograph. All the rest, of which taking a beautiful photo consist of, is extremely secondary in relation to the real of the photographic instant. (...) We photograph what we have seen, so we photograph ourselves. We place ourselves in a situation and from a certain point of view. (…) What we photograph is the fact that we take a photo.' 1 (Roche 77)

Seen in this way, the photographic act enacts the photographer in a place as a centre. Patricia Morosan's project Remember Europe - From The Middles is itself a search for the invisible centre: at once a geographical centre in the shifting sands of Europe and an interior centre - the 'here and now' of experience. In fact the entire project is based on a paradox: photographing what is not. As the borders of Europe change with the unfording of history, its centre is constantly de-placed, measuring the perpetual movement of Europe's policy of inclusion-exclusion. Chasing a non-existent centre, Patricia Morosan photographs it, in order to see it. Denis Roche considers that making visible is one of the essential functions of photography: 'Fixing a place through the capturing machine which is the camera (...) multiplies the visibility of the monument (...) We register through the camera in the fraction of an instant a mass of detailed information which is more complex than registering the place without the machine. (Roche 85).

Patricia Morosan's travel around former centres of Europe seems to be a story of the shifting construct 'Europe' – which is perceived as 'real' by being photographed. Through the possibility to be 'inside' the centre (but inside the photo too) the inhabitants of these always peripheral 'centres' assimilate their belonging to a territory. Nevertheless, every modification of frontier dislocates the centre, while cities and towns occupying these strategic points fall into desolation. Based on the belonging to the materiality of a delimited territory, the European identity remains without any concrete basis: the geographic indicator shifts, the idea of centre enters into local folklore and the monuments indicating it, corrode – as we see in Patricia's images.

Photographing 'what is not' creates a filmic reality. The project of Patricia Morosan can be seen as a sequence of answers to the question: what can the meaning of the centre be? The centre reveals itself as experienced by a subject – if it is the photographer herself or the inhabitants of the visited places. In fact rendering visible identitary constructions of these phantomatic ex-centres (with their always bypassed importance) remains invisible unless captured by elements exterior to the identity itself. Therefore Patricia Morosan constructs a multilayered project, which maps traces and connects various narratives. As the centre lingers in its periphery, the identity of these places appears in scattered images: the travels of Patricia, the photographic 'letters' of the town's inhabitants, the monuments with their histories and some fractured information on what did the same European centre mean and look like at different places.

***

CARTOGRAPHY calls the centre of a territory a barycentre. Nevertheless we cannot be sure if in the case of this project's hunt of European centres, we can talk about mapping, as each discovered centre is the barycentre of an inexistent map. This virtual map made only of centres notes the centrifugal movement of the photographer herself. But, more than any geographical map, it is the inscription of certain failed or attained values, projects, dreams, beliefs and norms of the communities she visited. A map is never neutral: it is used either to implement a state policy or to resist to it. French geographer Gilles A. Tiberghien talks about cartographic actions, rather than about maps. 'Even the official maps are the result of negotiations, of tensed exchanges of conflicting views, therefore they are fundamentally political' (Tiberghien 2017). He also talks about the fact that a certain cartographic vision will change the way its users experience real space. Maps have always been directly related to power, as we can learn from the convoluted history of Central and Eastern Europe where frontiers were drawn hastily on maps and strenuously assimilated by the population. In that way, as Jean Baudrillard famously said, the map preceeds the territory.

The project Remember Europe - From The Middles functions as a zooming in and zooming out of the same territory – a process in which we realize that a single map – in other words an official narrative – cannot pin down the shifting and redefinitions that haunt a politically troubled territory. From this project, we learn also that we can find a place on a map by searching around it, by identifying its relationships to other places, by viewing it through fragmented images, rather than by pointing to it and identifying it. It is what Patricia Morosan did in this project, where she collected data from various sources and recorded various interpretations on the same notion, bringing the abstract, bidimensional map into a representational narrative.

***

THE DESIRE OF BELONGING TO EUROPE IS IN FACT A CONSEQUENCE OF THE COLONISING POLICY OF THE WESTERN TOWARDS THE EASTERN EUROPE right after the dissolution of the Eastern Block, shows Mate Zombory (Zombory 2018) in his chapter of Centres of Europe. It is no coincidence that most centres of Europe are situated in Eastern Europe, where the 20th century history was most convoluted in the past 20th century.

The centre of Europe represented its aspiration of belonging culturally and politically to the West although geographically it was often integrated into the East. Geography is a mode of spatial representation, currently the dominant one. It therefore represents a knowledge rather than the reality as such – as Zombory states paraphrasing Michel de Certeau (Zombory 2018). The territory of the small towns that occupied various European centres becomes an indicator of these parallel stories of belonging.

As geography is an incontestable objective science, the value of European-ness passes to be perennial, in the name of maps as perennial entities. With the politics of the European Union after the Fall, the shifting territory of Europe is associated to this inclusion-exclusion politics into the domineering 'West'. The borders of Europe – in relation to which the centre is calculated – were seen as guarding the 'values' of Europe, while the East was felt as being 'outside'. Not only nations, but also places were striving to be 'integrated' if not into the European Union, than into the European territory.

Growing up in Romania, we can remember a popular saying right after the fall of communism, claiming the necessity that our country be finally 'appearing again on the map of Europe' – which obviously reinforces the authority of the European Union – as a return ticket to Europe. In this context, a geographically calculated centre can be felt as the ultimate proof of 'European-ness' no matter the cultural or political marginality of the village or town concerned. Belonging is defined by the body in authority while the symbolically charged idea of centre stands for sharing the power and recognition of those in authority.

***

Maps not only produce a knowledge over a territory but produce the territoy itself (Lambert 2018). In that sense it is interesting to study the agency of the place over its inhabitants. Patricia Morosan's peregrinations around the centres of Europe recall also practices of PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY – deambulations that record the effects of landscape on the psyche. Popular even among the Surrealists and Symbolists (Baudelaire's Flaneur) it was established as a cultural action by Guy Debord in 1955 connected to the Situationist Movement. Nevertheless it was only in the '90s that artists started to exercise psychogeography as an artistic practice and – like in Guy Debord's case – it was often connected to architecture and urbanism. Groups like the Italian urbanists Stalker searched to render a natural dimension to the more and more alienating urban life. As maps represent not only space, but also time, Patricia seems to walk on many maps at once: maps belonging to different historic moments (each with its own circumferences) layered like a palimpsest on the same geographical territory. These temporal domains are often conflicting as they are consequences of political disputes over territory, forced assimilations, and practices of domination, leaving behind a scattered and confused population. Patricia Morosan's psychogeographic project pastes on the abstract map the dimension of experience and knowledge and the social effects of political map-drawing become obvious. From this search of the spirit of the centre in a superposed piles of maps, a new cinematographic dimension results, challenging the bidimensionality of the map. She is mapping not so much historic events, but their consequences on a quotidian level, of often forced relocations, loss of property, lack of access to resources – the symptoms of the World Wars, Nazi terror, Stalinism, sovietisation and the attempts of redefinition in post-communism, which were experienced in Central Europe.

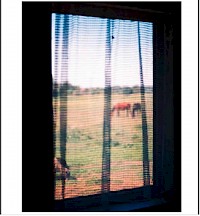

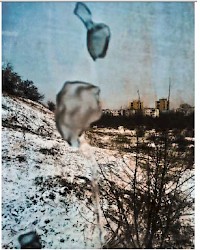

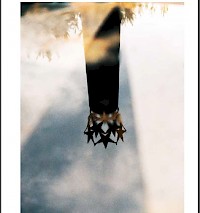

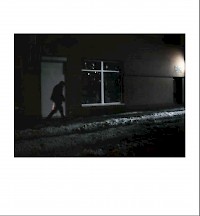

By giving a single-use camera to an inhabitant of each 'centre' she visited, Patricia Morosan collected their shots (calling them LETTERS), which construct a narrative of the quotidian. These images exhibit once again the invisibility of our subject (the centre) as they show people, moments and places like any other. They are in a way a proof of the discontinuity between representation and experience. A slight anxiety is hovering over these nebulous images which seem to lack references. The preciseness of cartography gets blurred, the image stays open and the centre melts into the all-encompasing periphery. The photographs by the inhabitants can be seen as a sort of 'counter-mapping', shot by the ones excluded from borderdrawing and mapmaking. The resulting image cannot be other than divergent from nation-state narrative. Beside a playful dimension in this belief in 'the persisting centre', the photographs of these desolated centres show more than anything a face of Europe. With their crude directness they nevertheless make us also remember the statament of Denis Roche regarding the violence of every image. They evoke a fragmented history, where cultural and social continuity was periodically cut down by new waves of occupation and repressions, coming either from the East or from the West.

But Patricia Morosan is not alone in her peregrinations through Central and Eastern Europe. She has an homologue in the main character of Twelve Circles, the 2005 novel of Ukrainian writer Yuri Andrukhovych – photographer Karl-Joseph Zumbrunnen. He travels in the '90s in search of the 'heart of Europe' with the never materialized aim of showing his travel-photos in an solo-exhibition with the title 'Europe: the Decentred Centre'.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Yuri Andrukhovych. 2005. Twelve Circles. Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, London

Leopold Lambert. 2018. Cartography and Power in The Funambulist Magazine nr 18/2018

Denis Roche. 2016. La disparition des Lucioles. Reflexions sur l'acte photographique. Seuil. Fiction&Cie, Paris.

Gilles A. Tiberghien. 2017. Les cartes representent aussi ce qui n'existe pas, elles dinnent acces a l'imaginaire de l'autre. Liberation / Juillet 2017

Mate Zombory. 2018. Centres of Europe in Marcin Moskalewicz and Wojciech Pryzbylski (Ed.). Understanding Central Europe. Routledge. New York

1My translation from the French originial